These long form articles are part of a series in which I go through the book ‘R for Data Science’ and document my learnings and understanding of concepts in R in my own way.

The basics of data visualisation

We start with the fun part, exploring and visualizing data. This is considered by many to be the biggest pay-off when it comes to learning R and provided me with loads of motivation to keep learning more and more, and to be able to produce better looking graphs as a result.

To start of, we’re going to need to load only the tidyverse.

library(tidyverse)

## -- Attaching packages --------------------------------------- tidyverse 1.3.2 --

## v ggplot2 3.3.6 v purrr 0.3.4

## v tibble 3.1.8 v dplyr 1.0.9

## v tidyr 1.2.0 v stringr 1.4.0

## v readr 2.1.2 v forcats 0.5.1

## -- Conflicts ------------------------------------------ tidyverse_conflicts() --

## x dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

## x dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

Note that the tidyverse loads eight packages and lists their current

version number. If you don’t see the message above you have to install

the package first (install.packages("tidyverse").

You also see conflicts: some functions are provided in two packages. You

could specify which exact function from a package you would like to use

by using package::function() like so ggplot2::ggplot().

Now let’s load up a data set about fuel usage for different types of

cars (mpg) which comes with the tidyverse.

mpg

## # A tibble: 234 x 11

## manufacturer model displ year cyl trans drv cty hwy fl class

## <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <chr> <chr>

## 1 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 auto~ f 18 29 p comp~

## 2 audi a4 1.8 1999 4 manu~ f 21 29 p comp~

## 3 audi a4 2 2008 4 manu~ f 20 31 p comp~

## 4 audi a4 2 2008 4 auto~ f 21 30 p comp~

## 5 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 auto~ f 16 26 p comp~

## 6 audi a4 2.8 1999 6 manu~ f 18 26 p comp~

## 7 audi a4 3.1 2008 6 auto~ f 18 27 p comp~

## 8 audi a4 quattro 1.8 1999 4 manu~ 4 18 26 p comp~

## 9 audi a4 quattro 1.8 1999 4 auto~ 4 16 25 p comp~

## 10 audi a4 quattro 2 2008 4 manu~ 4 20 28 p comp~

## # ... with 224 more rows

## # i Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

The mpg data set has 11 columns containing variables and 234 rows

containing observations. Now we create our first plot.

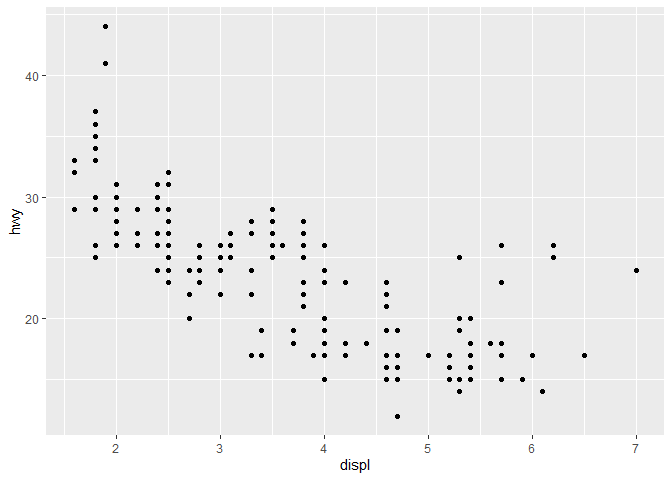

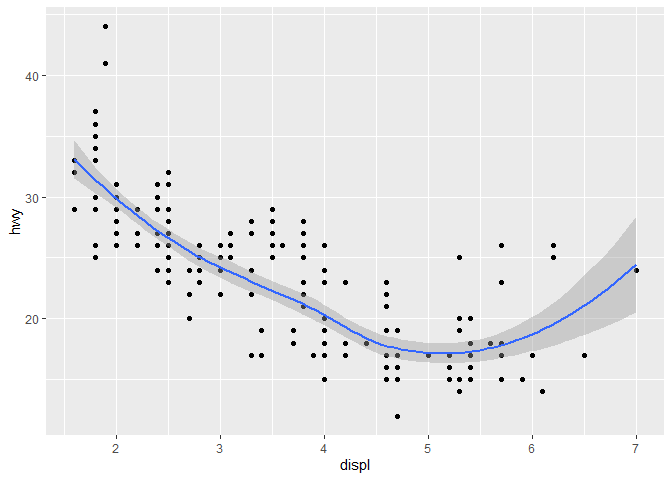

Mapping variables to the X and Y axis

Engine displacement (displ) versus highway miles per gallon (hwy).

We can map aesthetics to variables via the ggplot package. You can do

this explicitly like so:

# explicitly telling ggplot what to use

ggplot(data = mpg) +

geom_point(mapping = aes(x = displ, y = hwy))

The class variable of the mpg data set classifies cars into groups

such as compact, midsize, and SUV. If the outlying points are hybrids,

they should be classified as compact cars or, perhaps, subcompact cars

(keep in mind that this data was collected before hybrid trucks and SUVs

became popular).

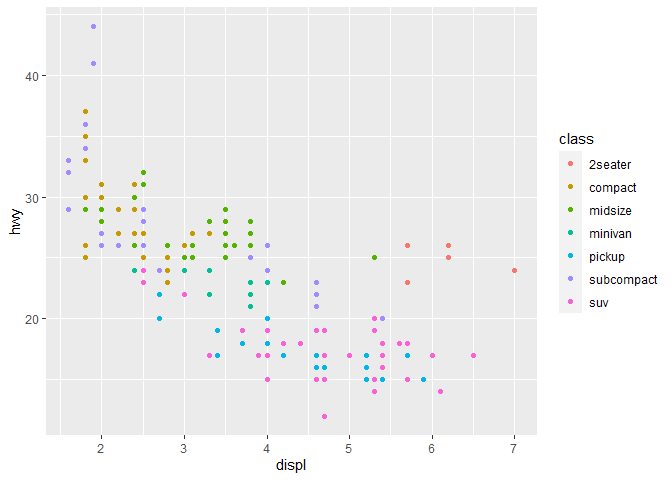

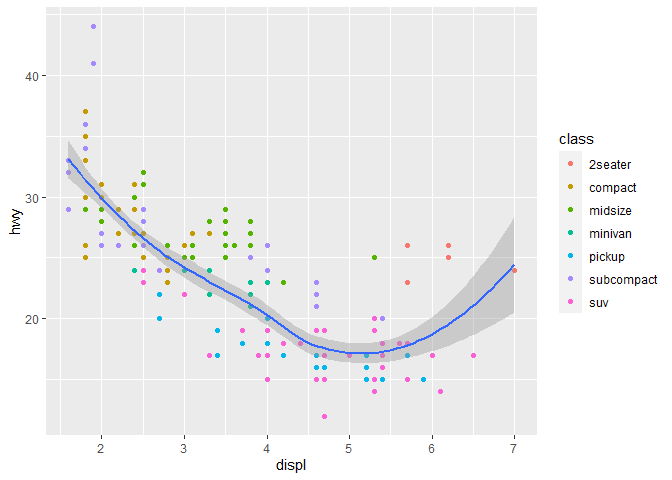

You can also map the colors aesthetic to the class variable. Here we

will use the tidyverse way and make use of the pipe operator (%>%).

The pipe tells whatever is on the right side, to take everything on the

left side, and use it as input for the first argument on the right

side. Your code becomes shorter and more intuitive to read.

# using the pipe operator the tidyverse way

mpg %>% # take mpg and use it for the first argument on the right side

ggplot(., aes(displ, hwy, color = class)) +

geom_point()

The dot character in

ggplot(., aes(displ, hwy, color = class))represents the location of the first argument and is wherempggets piped into. You can omit this as it is always the first argument after a%>%.

Mapping variables to aesthetics

Besides the X and Y axis (which are also aesthetics) there are several other aesthetics you can map variables to.

- color

- shape

- alpha; transparency

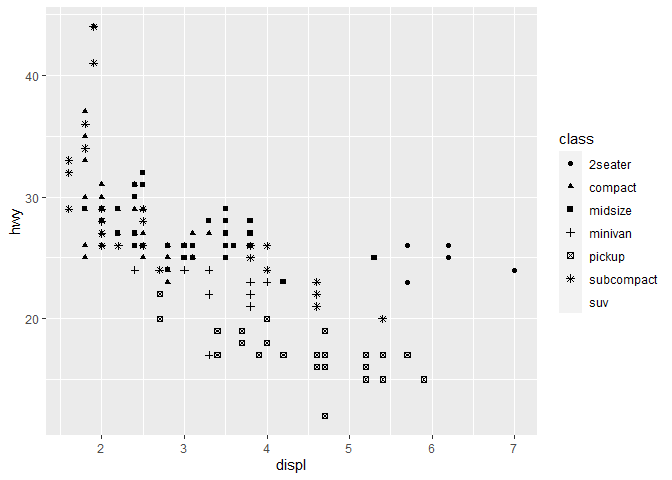

Shape

We can also map the class to the shape aesthetic:

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy, shape = class)) +

geom_point()

## Warning: The shape palette can deal with a maximum of 6 discrete values because

## more than 6 becomes difficult to discriminate; you have 7. Consider

## specifying shapes manually if you must have them.

## Warning: Removed 62 rows containing missing values (geom_point).

Note the warning: shapes are more difficult to compare than colors. Unless explicitly specified, 6 shapes are included in the base plot. In this case we have 7 unique values for the

classvariable and the SUV class has no shape assigned.

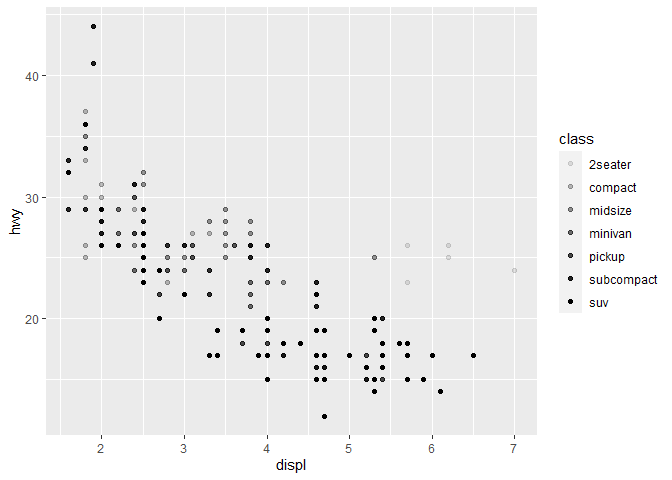

Alpha

For instance, if we map the class variable to the alpha aesthetic -

controlling the transparency of the points - the results are not as

clear.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy, alpha = class)) +

geom_point()

## Warning: Using alpha for a discrete variable is not advised.

The class variable is discrete and the alpha aesthetic is not best

suited to highlight this.

Color and shape are better suited to display categorical variables while size and alpha are better used for continuous variables.

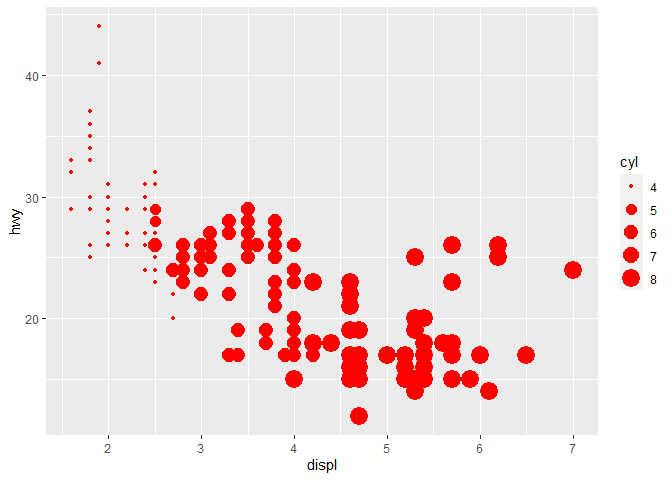

You can also manually set specific aesthetics for a geom. You do this

inside of the geom_point() function.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy, size = cyl)) +

geom_point(color = "red")

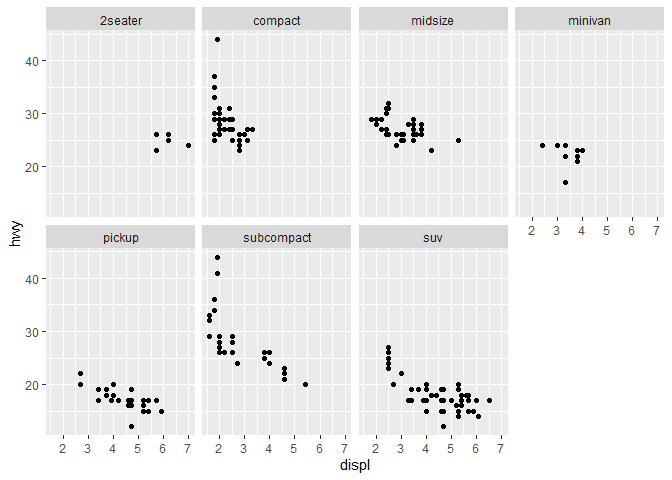

Facets

When dealing with categorical variables, facets are quite useful and

display their own subset of data. You can use facet_wrap() to facet

your plot with a single variable. The first argument that goes into

facet_wrap() is a discrete variable and is prefixed with the ~

character.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) + # plot displacement versus highway miles per gallon

geom_point() + # add point geometry

facet_wrap(~ class, nrow = 2) # facet by class and use only 2 rows for the data

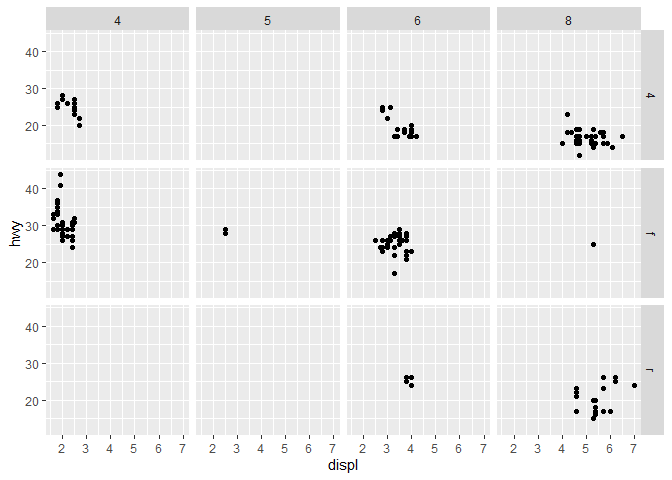

If you want to plot against two discrete variables, you can use

facet_grid(). You use two variable names, separated by a ~.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) + # plot displacement versus highway miles per gallon

geom_point() + # add point geometry

facet_grid(drv ~ cyl) # facet by drive and cylinders on x and y axes

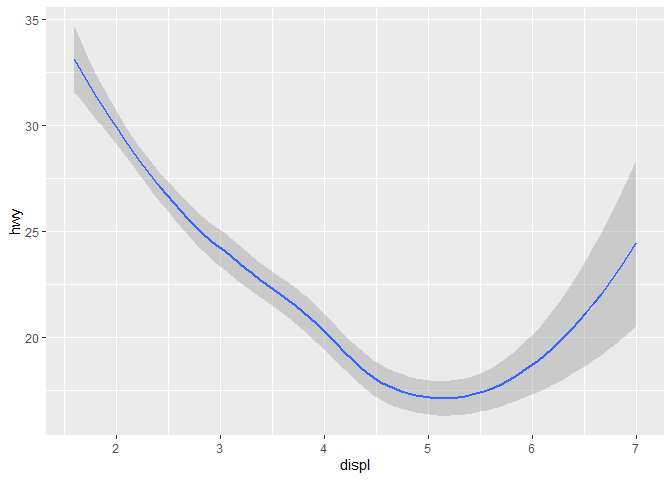

Geometric objects

Up until now we have only used the geom_point() geom to plot and show

data. There are other options that you can use. Instead of

geom_point() you might use geom_smooth(), which creates a smoothed

line chart.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_smooth()

Both visualizations represent the same variables on the x and y axis and

are based on the same dataset. With ggplot(), you can use different

geoms to visualize your data. Every geom object takes a mapping

argument but not every aesthetic will work with every geom. You may

decide the shape of a point by using geom_point(shape = 5) but you

can’t set the shape of a line like that.

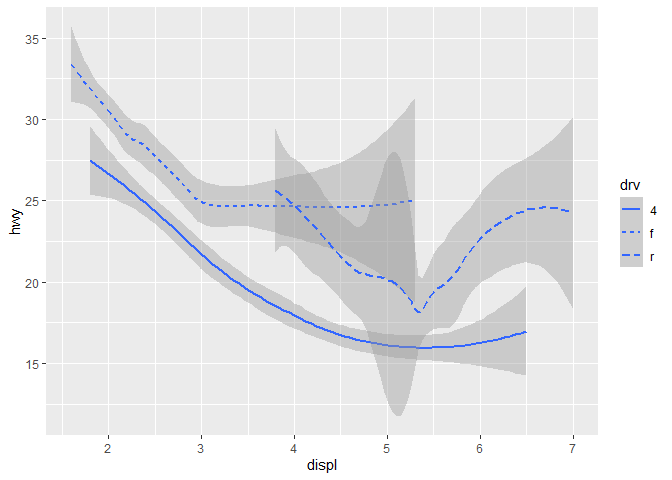

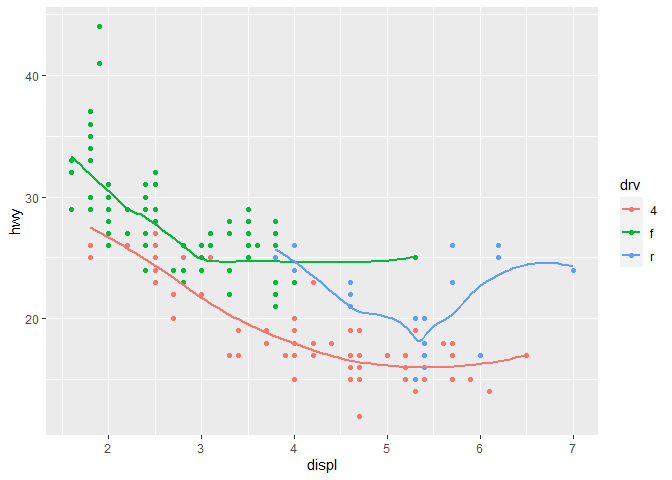

However, instead of using the shape aesthetic, you can use the linetype aesthetic to draw a different line for the unique variable that you map to linetype.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_smooth(aes(linetype = drv))

In this plot we see the lines associated with their drv values, which

stands for a car’s drivetrain (the group of components that deliver

mechanical power from the prime mover to the driven components). We see

a line for 4-wheel drive, front-wheel drive and rear-wheel drive.

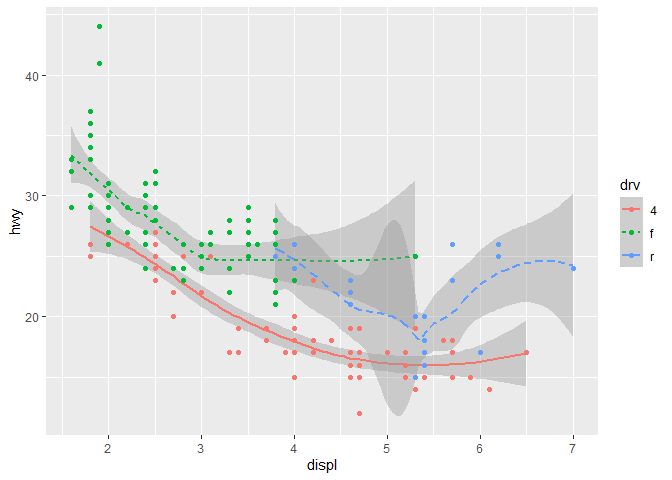

But where are the original points? To make it more clear, you can simply

add the points by adding another geom. Everything you define in the

first aes() function inside ggplot() is applied on all geoms. In

the case below we color both the line and the points by their drv

value and we define specific linetypes for the geom_smooth()

component.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy, color = drv)) +

geom_smooth(aes(linetype = drv)) +

geom_point()

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

You can add multiple geoms to a plot to make absolutely insane graphs.

There are over 40 geoms in ggplot2 and if you use additional extensions

to the tidyverse you get

even more. Take a look at the ggplot2

cheatsheet

and if you want to learn more about a specific geom, use ?geom_smooth.

Unlike geom_point(), which maps an observation (a single row of data)

to a single point, geoms such as geom_smooth() map a whole set of

observations (multiple rows of data) to a single object (a line chart).

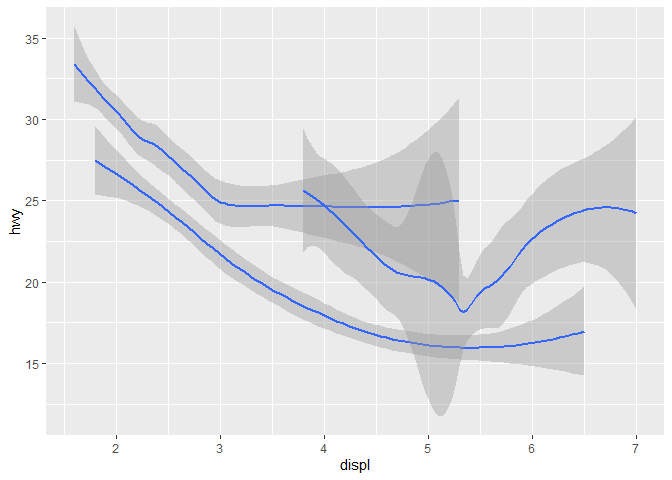

# mapping a variable to a group doesn't add any aesthetic properties like color or size to the plot

mpg %>%

ggplot() +

geom_smooth(aes(displ, hwy, group = drv))

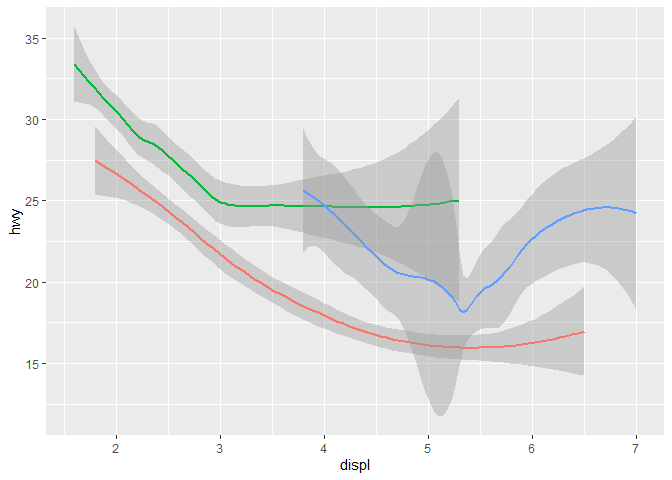

# mapping a variable to an aesthetic like color obviously does

mpg %>%

ggplot() +

geom_smooth(aes(displ, hwy, color = drv),

show.legend = FALSE

)

Multiple geoms

Simply add more geoms to the plot when you want to add more geometric

elements. You may choose to map your variables inside the different

geoms or in ggplot2. You may see some duplicate code if you decide to

map inside the geom functions.

# duplicate mapping

mpg %>%

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_smooth(aes(displ, hwy))

These mappings are overruled if you explicitly specify another mapping

inside the geom functions. Mapping variables to aesthetics inside the

ggplot() function are seen as global mappings and apply to all

geoms.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) + # global mappings

geom_point() + # empty mapping

geom_smooth() # empty mapping

You can add a specific mapping to a single geom only. In this case we

map color to the class variable.

# adding color mapping to geom_point only

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_point(aes(color = class)) +

geom_smooth()

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

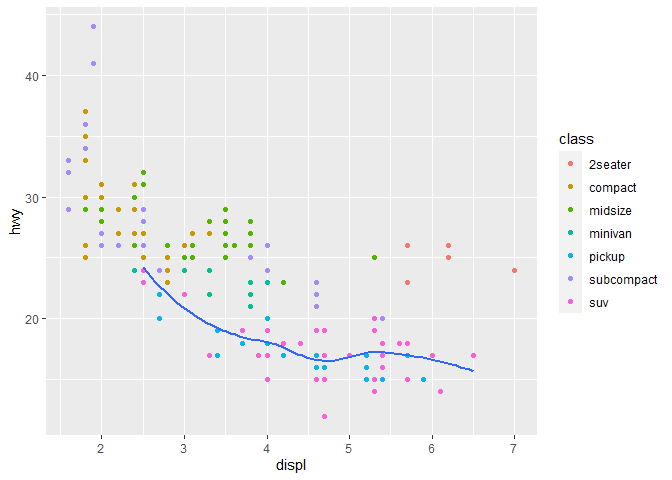

You can also show a subset of the data for different layers (geoms). In

this next plot, the smooth line represents a subset of the class

variable. We only show the geom_smooth() for the suv class. You can

remove the shaded area representing the standard error (se) by adding

se = FALSE to the geom.

mpg %>% ggplot(aes(displ,hwy)) +

geom_point(aes(color = class)) +

geom_smooth(data = filter(mpg, class == "suv"), se = FALSE, show.legend = FALSE)

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

Note that inside the

geom_smooth()function, an explicit call todata = filter(mpg, class == "suv")is required as you are adding layers and no longer piping the data with%>%.

ggplot(data = mpg, mapping = aes(x = displ, y = hwy, color = drv)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE)

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

Statistical transformations

So far, we have looked at functions that plot the data as-is and do

not perform any mutations or statistical transformations on the data

itself, such as creating new variables. In this section we’re going to

look at bar charts with geom_bar().

We are using the diamonds data set which comes with ggplot2. It

contains 10 variables for 53940 observations of diamonds.

diamonds

## # A tibble: 53,940 x 10

## carat cut color clarity depth table price x y z

## <dbl> <ord> <ord> <ord> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.23 Ideal E SI2 61.5 55 326 3.95 3.98 2.43

## 2 0.21 Premium E SI1 59.8 61 326 3.89 3.84 2.31

## 3 0.23 Good E VS1 56.9 65 327 4.05 4.07 2.31

## 4 0.29 Premium I VS2 62.4 58 334 4.2 4.23 2.63

## 5 0.31 Good J SI2 63.3 58 335 4.34 4.35 2.75

## 6 0.24 Very Good J VVS2 62.8 57 336 3.94 3.96 2.48

## 7 0.24 Very Good I VVS1 62.3 57 336 3.95 3.98 2.47

## 8 0.26 Very Good H SI1 61.9 55 337 4.07 4.11 2.53

## 9 0.22 Fair E VS2 65.1 61 337 3.87 3.78 2.49

## 10 0.23 Very Good H VS1 59.4 61 338 4 4.05 2.39

## # ... with 53,930 more rows

## # i Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

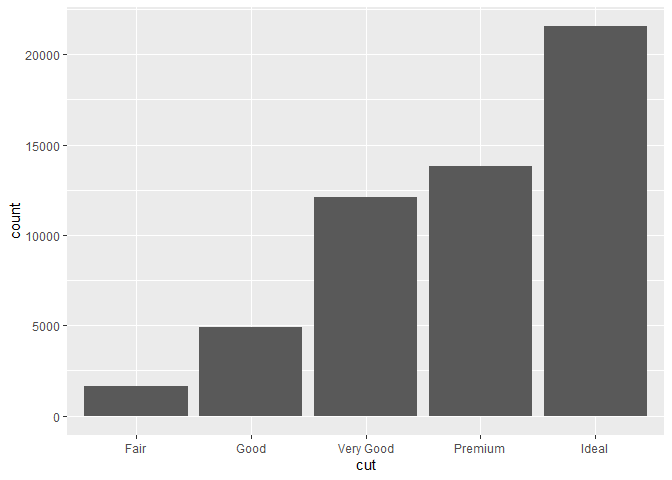

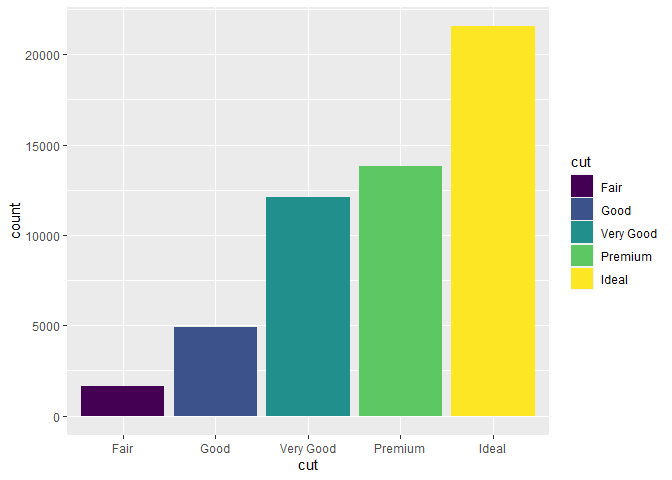

A bar chart takes a specific variable and performs a count() of all

the unique observations in that variable. In this case, cut ratings

ranging from fair to ideal.

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(cut)) +

geom_bar()

Here are some examples of how different geoms transform the data prior to creating the plot:

- bar charts, histograms, and frequency polygons bin your data and then plot bin counts, the number of points that fall in each bin.

- smoothers fit a model to your data and then plot predictions from the model.

- boxplots compute a robust summary of the distribution and then display a specially formatted box.

The transformations are performed under the hood in the so-called ‘stat’

functions. You can inspect the stat function of a specific geom by

typing ?geom_bar. You see that stat = 'count'. Every geom has their

own stat function:

?geom_point:stat = 'identity'?geom_boxplot:stat = 'boxplot'?geom_smooth:stat = 'smooth'?geom_bar:stat = 'count'

Usually you can use geoms such as geom_bar() and their respective

transformation stat_count() interchangeably. In some cases you might

want to use a specific geom but use another stat function or use a stat

function instead of a geom.

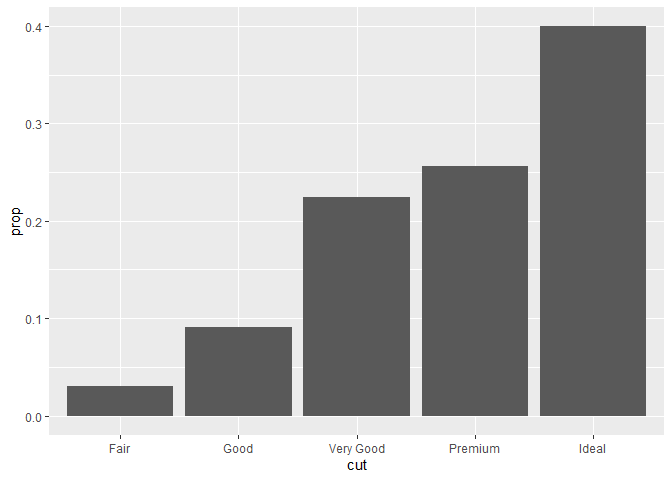

Here we use geom_bar() and a stat function to map proportions to the

y-axis. If you leave group = 1 out all proportions will be equal to 1

or 100%. The bar geom will count all rows or observations with a

specific cut, totalling 100% for each level. You override this behaviour

by adding a dummy group such as group = "whatever". Then the correct

proportions over all observations will be used.

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(aes(cut, after_stat(prop), group = "whatever"))

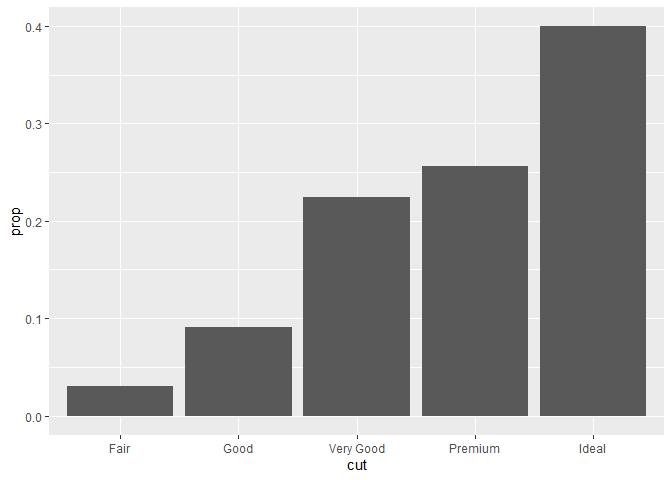

Here we use stat_count() to get the same results:

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

stat_count(aes(cut, after_stat(prop), group = 1))

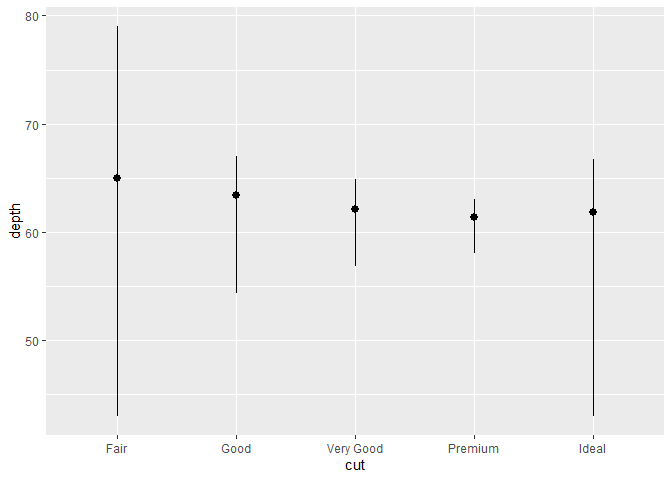

You can use other stats for a succinct summary of the data too, such as stat_summary

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(cut, depth)) +

stat_summary(mapping = aes(cut, depth),

fun.max = max,

fun.min = min,

fun = median)

Note that this comes close to what geom_boxplot() (a statistical

summary) actually looks like. You can work around the default

functionality provided by all the geoms when you start using stats for

additional customization. I must say, geoms very often prove sufficient

for your everyday needs (so far, they have for me).

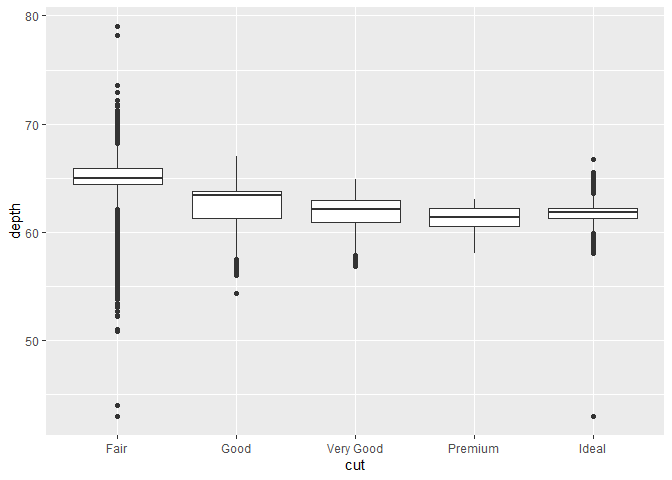

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(cut, depth)) +

geom_boxplot()

The boxplot reveals important information regarding the distribution of your data, such as:

- the median value

- the upper and lower quartile (Q1 and Q3) range

- the interquartile range (difference between Q1 and Q3)

- minimum and maximum values

- outliers

Position adjustments

When it comes to bar charts there is another tweak you can perform in order to change how the bar chart is displayed. You can fill with a color and map the color to a variable.

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(aes(cut, fill = cut)) # fill the bars with color based on the different cuts

There are a few noteworthy position adjustments for bar charts:

There are a few noteworthy position adjustments for bar charts:

"stack""identity""fil""dodge"

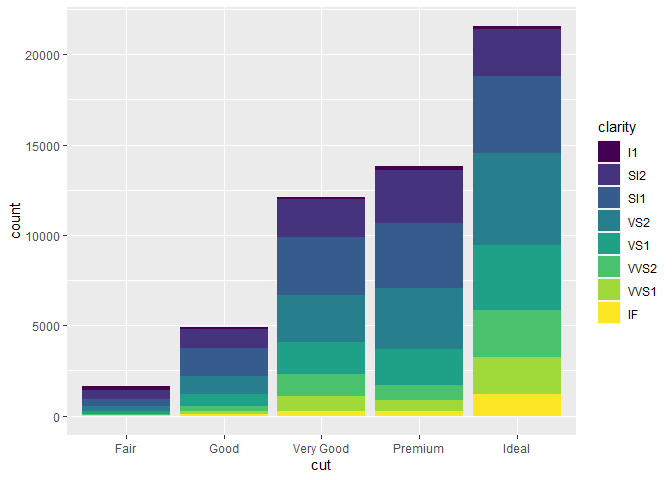

Stack

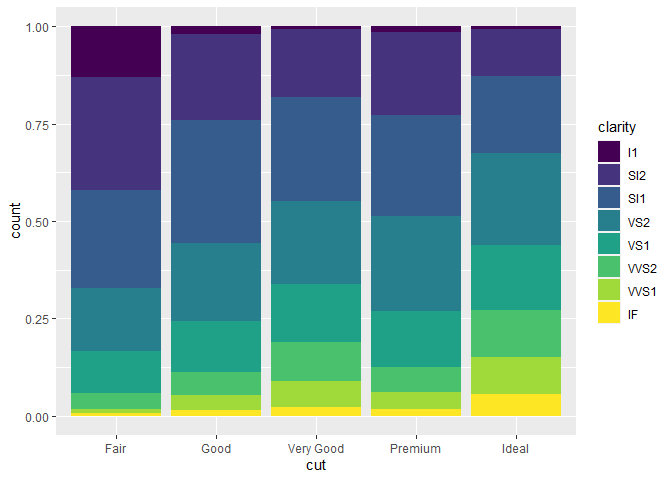

You can add another variable by mapping fill to something else then

cut, let’s say clarity. Now we add mapping (fill) for every subset

of clarity for the different cuts available. The default position for

geom_bar() is "stack".

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(aes(cut, fill = clarity), # add mapping (fill) for every subset of clarity in available cuts

position = "stack") # this is the default position for geom_bar() but it needs another variable in order to fill!

The way these bars are stacked is performed automatically by the

position adjustment which is specified by the position argument

inside geom_bar(), the default position is "stack". It stacks the

counts for all subsets of cuts and fills by clarity.

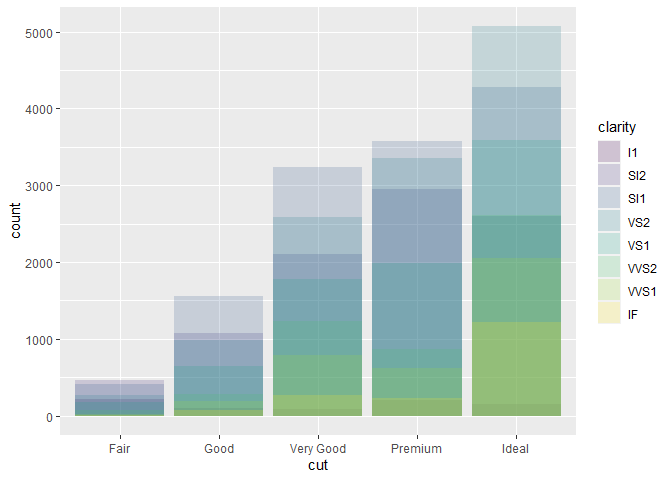

Identity

The "identity" position shows the data exactly where it would lie in

the graph itself. It is not useful for bar charts and is the default

position for 2d geoms like geom_point(). For bar charts, the

"identity" position causes the segments to overlap because it counts

all different subsets and plots the colored bars over each other.

diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(cut, fill = clarity)) +

geom_bar(alpha = 1/5, position = "identity")

Fill

The "fill" position works just like the "stack" position but makes

all the different bars equal height. This makes it easier to compare the

proportions between groups.

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(aes(cut, fill = clarity), position = "fill")

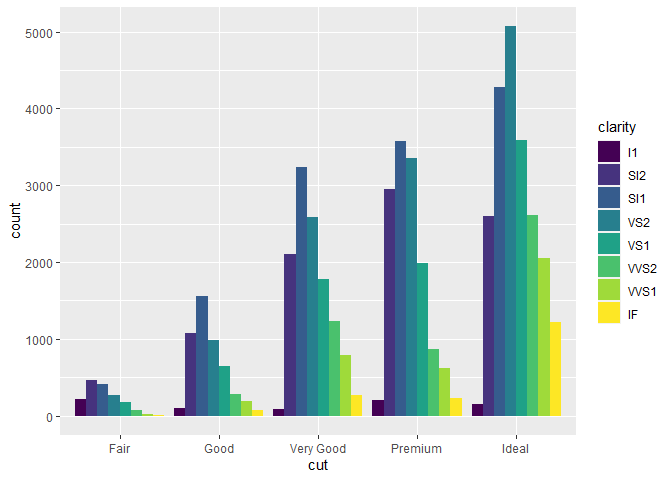

Dodge

The "dodge" position places all objects side by side which makes it

easier to compare the values per group.

diamonds %>%

ggplot() +

geom_bar(aes(cut, fill = clarity), position = "dodge")

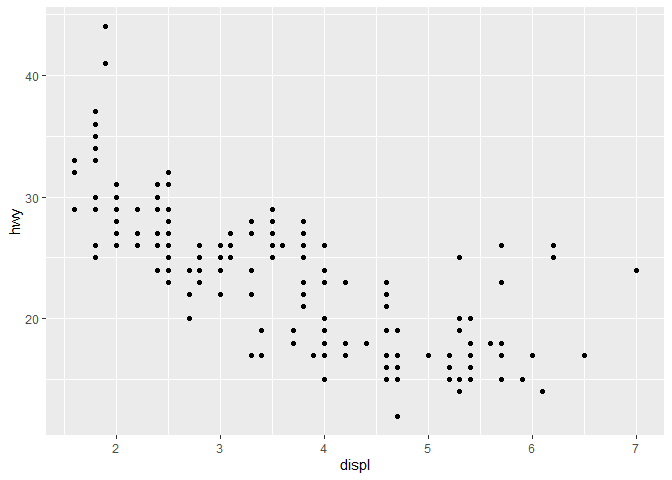

Jitter

There is another type of position adjustment that is quite handy. Not for bar charts but for scatter plots. In the first plot that we made, many of the individual points were overlapping. We note 234 observations. If you would count the individual points you wouldn’t arrive at this number. This problem is called overplotting and it is caused by rounding so the points appear on the grid used by ggplot.

nrow(mpg) #count rows in mpg dataset

## [1] 234

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_point()

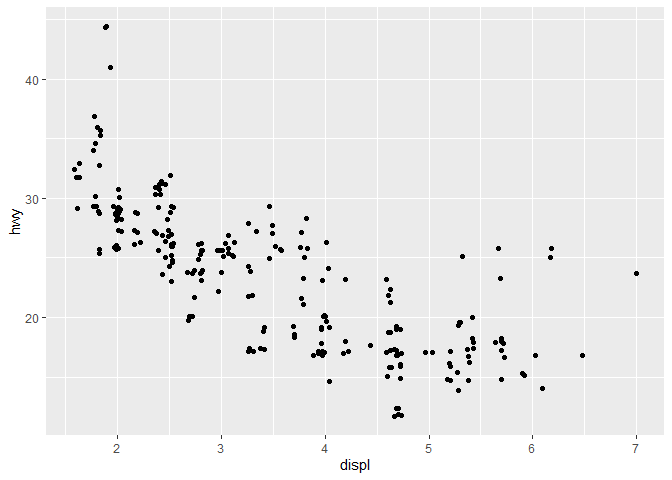

You can avoid this grid by using position = "jitter" which adds random

noise to all the points. There is even a shorthand for this position

specifically, geom_jitter(). Note the randomness applied to all points

in both graphs. Take care with this position adjustment at small scales

as it makes your graph less accurate. It can be quite revealing on

larger scales and with lots of data to work with.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(displ, hwy)) +

geom_point(position = "jitter") # or use geom_jitter() instead

Coordinate systems

Another aspect of building graphs is the coordinate system. The standard coordinate system used is the Cartesian system. In the Cartesian system, the X and Y axis act independently to determine the location of the data (go along the X axis, then up along the Y axis).

There are a few other coordinate systems that might be useful on the rare occasion:

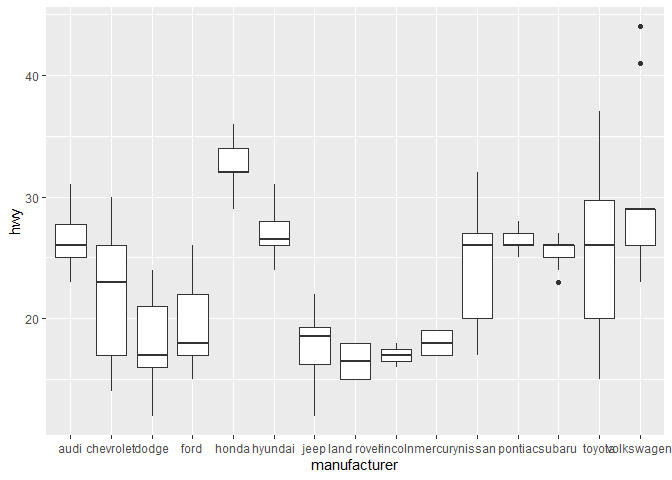

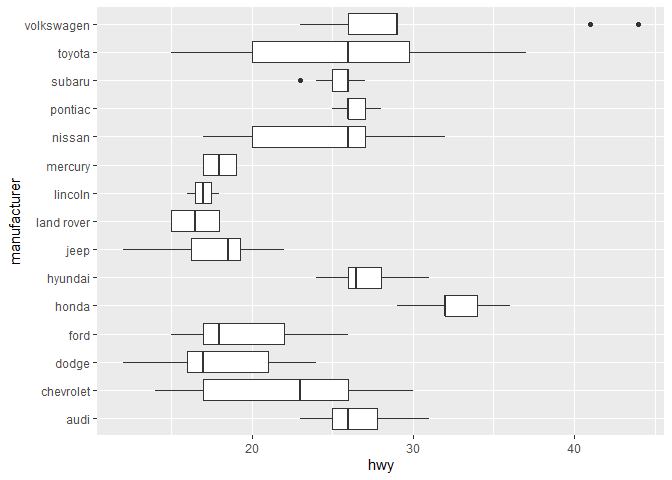

coord_flip(): swaps the X and Y coordinates, very usefull for data with a lot of groups and labels (specifically longer labels)!

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(manufacturer, hwy)) +

geom_boxplot()

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(manufacturer, hwy)) +

geom_boxplot() +

coord_flip()

Note that you can also achieve the same result by flipping the X and Y aesthetic! I didn’t realize this until quite recently.

mpg %>%

ggplot(aes(y = class, x = hwy)) + # instead of aes(x = hwy, y = class)

geom_boxplot()

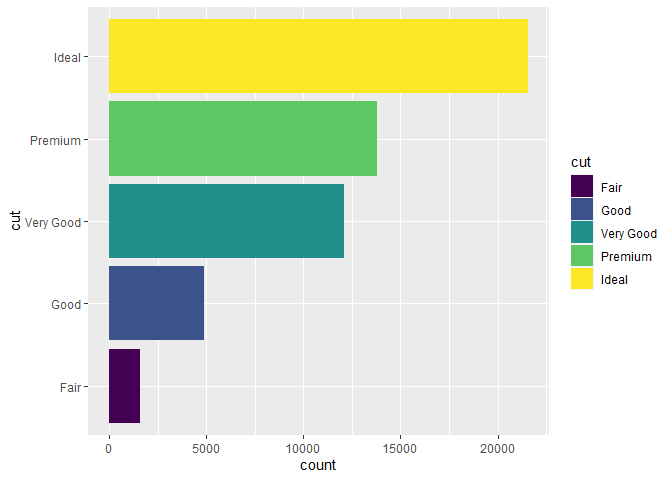

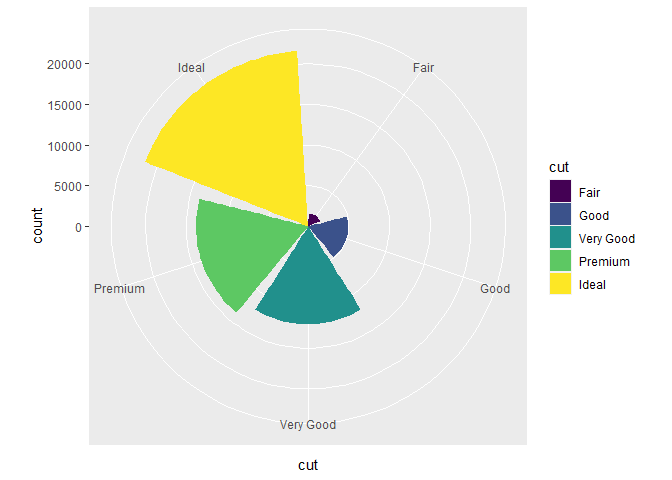

coord_polar(): uses polar coordinates in which each point on a plane is determined by a distance from a reference point and an angle from a reference direction. The polar coordinate system is probably most often used to make pie charts.

chart <- diamonds %>%

ggplot(aes(cut, fill = cut)) +

geom_bar()

chart + coord_flip()

chart + coord_polar()

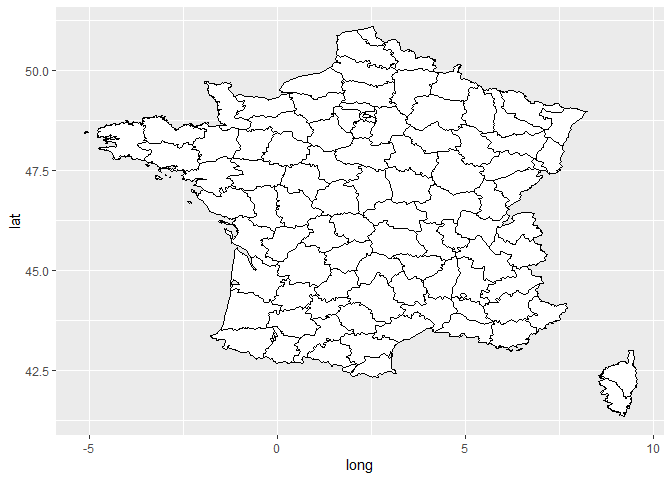

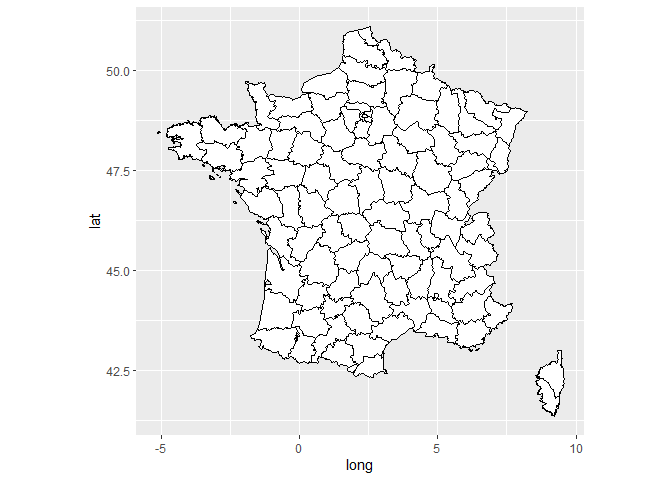

coord_quickmap()is used when plotting spatial data such as maps to set the correct aspect ratios. You can clearly see the difference in the plots of France below.

#library("maps")

map <- map_data("france")

ggplot(map, aes(long, lat, group = group)) +

geom_polygon(fill = "white", color = "black")

ggplot(map, aes(long, lat, group = group)) +

geom_polygon(fill = "white", color = "black") +

coord_quickmap()

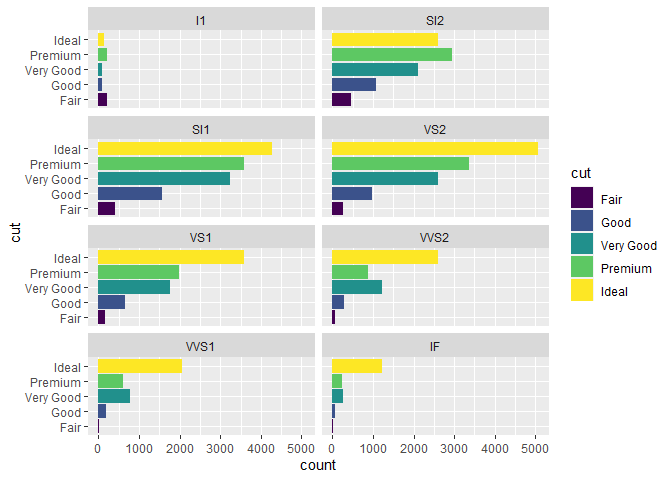

The layered grammar of graphics

We’ve demonstrated that you build graphics using different layers. This way of visualizing data has been dubbed the grammar of graphics. Ultimately, the template for this is (the tidyverse way):

diamonds %>% # specify the data you wish to use and pipe it in

ggplot(aes()) + # call the ggplot function and set global mapping if required

geom_bar( # use a specific geom for your plot

mapping = aes(cut, fill = cut), # set specific aesthetic mapping for the geom

stat = "count", # specify the stat used by the geom

position = "stack" # specify the position adjustments for the geom

) +

coord_flip() + # specify another coordinate system

facet_wrap(~clarity, nrow = 4, ncol = 2) # faceting by clarity in four rows and 2 columns

Remember, most often the default stat or position will work for you. There are cases where you want to overwrite or customize your graph and this knowledge will proof essential to manipulate your graph to your liking.